(10-Minute read)

In the summer between Year 11 and 12 of high school, I spent three months in Africa. My aunt and uncle were missionaries in Tanzania and I stayed with them in their home in Dodoma. Over Christmas, they took a break and we all shared a room in a missionary guesthouse in Kenya. We ate mangoes from the trees and saw lions at a nearby game park. We saw Handel’s Messiah performed by an all-African choir in a sandstone church. I was nearly 17, clueless and naive in the way of young people of the 80’s and pre-internet. An idealist and a romantic with a good dose of Pentecostal fervour.

Back then the airlines allowed smoking in-flight and I turned up in transit in what was still called ‘Rhodesia’ on my plane ticket, full of allergies and knocked around from jet lag. I had only flown once before, Sydney to Melbourne, and could hardly stand up straight or string a sentence together. On the flight to Dodoma, I played ‘Do they know it’s Christmas’ on repeat on my cassette Walkman, feeling very Live Aid about being in Africa. I’m not kidding.

I remember rationing toothpaste and driving for half an hour for water every few days. There were police with huge guns at the bank in town; I had never seen a gun before. Regular visits to the local market forced me to consider, for the first time, that fresh produce came from the gardens of people who grew it. I had always been able to just get a banana from my well-stocked fruit bowl.

As a nurse, there were people lining up for my aunt’s attention each morning; she cared for three babies in the next room to mine the whole time I was there. I woke one morning to learn one of them had died.

They had a humble home but a lush garden full of colourful flowers, and when the electricity was working my aunt baked cakes in her much-loved enormous microwave. Processed food wasn’t available and we ate what was grown or able to be bought on any given day. It was good; fresh bread, fresh fruit and veg. I didn’t miss the junk.

One afternoon I wandered off to the nearby football field and, despite there not being a body of water in sight, stripped down to my swimmers, poured reef oil all over my body and lay on the bench seats to bake. Before too long I found myself surrounded by a group of wide-eyed young men trying to proposition me in Swahili. My little cousin soon found me and went running to bring my aunt whose face I still remember. She shooed them away then spent some time trying to figure out how to explain to me why what I had just done was all kinds of culturally inappropriate, and how the boys had thought I was a sex worker.

My time there was formative to say the least.

From the 1980’s onwards I have done stupid things with the most innocent and well-meaning of intentions. More than this, I felt called and compelled with the urgency of Christian service.

I was always the one bringing home the misfits, serving coffee to trans ladies of the night in Kings Cross and generally feeling very earnest about ways I could serve. My time in Africa had pulled me in to the dream of missionary work as a vocation and I bought into the exotic ‘otherness’ with all my heart.

At church I sang songs about being ‘sent,’ one in particular that belted out a promise from God: “ask of Me and I will give the nations as an inheritance for you.” The sense of responsibility—colonial leanings notwithstanding—was powerful. I finished school and went to Bible College.

Bless my young, sweet self … I was going to save the world.

When my kids came along in my twenties, I wanted them to learn to be generous, I wanted them to grow in an understanding of their privilege, to appreciate all they had. We sponsored children and memorised verses like “speak up for those who cannot speak up for themselves and for the rights of the oppressed and needy.” We packed those shoeboxes filled with plastic toys and toothbrushes to send to poor children in overseas communities. My daughter and I cried at footage of Oprah gifting Christmas presents to hundreds of South African children that time. You know the episode, you saw how their faces lit up.

I hoped when my kids were teenagers, they would choose to go on short-term mission trips, perhaps to teach English or help build a school. It didn’t occur to me that they weren’t qualified to do this.

In the days before Instagram, I dreamt of Nat Geo-style photos in remote villages, placing myself in the centre of grateful people, the lighting just so. Perhaps in a t-shirt with an inspirational quote.

And what could be wrong with any of this? It sounds like plenty of people you know, I bet. Maybe you recognise yourself in it.

We are wired for relationship and community. It’s in our DNA to want to help others, and those of us who rate highly on the empathy scale are grieved by the pain of the world and often find our way to decades of service.

Those of us with a justice bent work to address systemic wrongs and advocate for those who find themselves crushed under the weight of these.

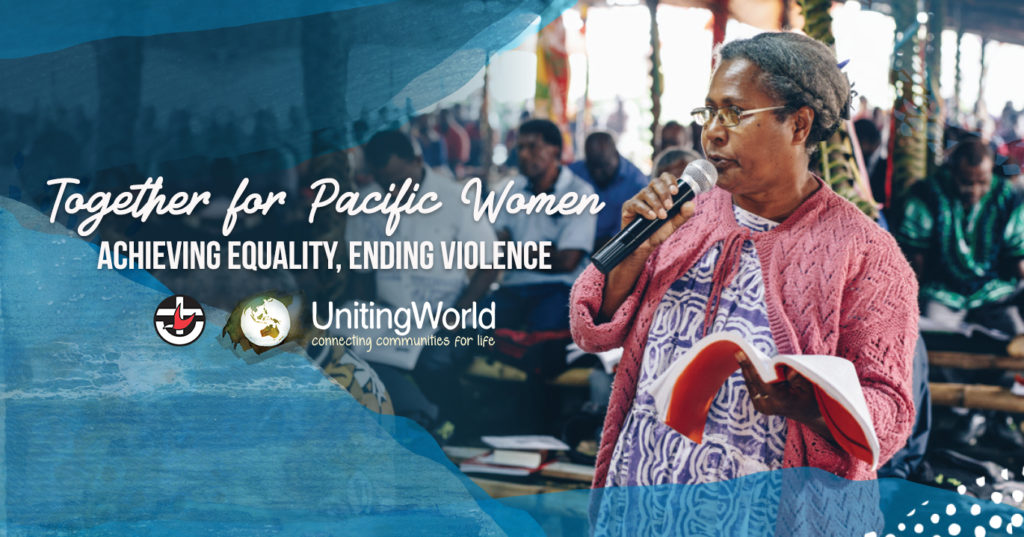

And we should. The world is a harsh and unjust place. If we have power we should use it. At UnitingWorld, our team works to support those who are making things better in their context. I will do this till I am old and grey.

But what I have learnt, gradually, awkwardly and with a good deal of humility is that I am not and should never have been at the centre of this.

I thought I had to take God to unreached people groups and serve them in their poverty. I have since learnt that God is already there, and in many cases people already have all they need. Where they don’t, local groups are best placed to serve their own people.

I thought the Western consumer model of ‘the more you have – the more blessed you are’ needed to make its way to the slums. I have learnt we in the West are poorer than many who have very little.

In saying this I don’t want to romanticise poverty, it can be crippling and brutal. In my work I support local partners who are working to connect people with their human right to a dignified life. But what I see is people who don’t believe they are entitled in the way we in the West do, who measure richness by relationships, hairstyles and henna and celebrating seasonal rituals, growing their own food and bearing healthy children.

In our attitudes and the posture we take when working overseas, especially (especially!) when faith and a sense of calling is involved, I have learnt we need to be students. We will never arrive at having it all figured out; how could we? It’s not our context. We are there as guests and allies, not decision makers.

Never is this more true than after an emergency. Emotions run high and compassion and grief move us to respond. Local partners in the Pacific told me after one disaster they didn’t have the funds to receive a container from the port and were forced to spend money allocated to a post-cyclone rebuilding project to receive the unwanted-and-unasked-for goods, which they then burnt as they had no use for them. On another occasion, a team of blokes wondered what they would do with boxes of second-hand bras. Perhaps this sounds ungrateful on their part. But have you ever wondered, after a trauma, what to do with a large, expensive-to-send but not really valuable gift you have no use for and didn’t want?

Often these containers just turn up. When overseas groups do ask, I wonder if they consider the power imbalance and the cultural implications of people being able to refuse? Even in the asking; “how can we help, what do you need, how can we support you,” is better than – “I have a crate load of bikes, would you like me to send them over?” And sending second-hand clothes? The ugly pieces that are stained or have a tear. My friend in Fiji was offended after losing everything in cyclone Winston. “We still have our dignity”, she said.

We give in ways that feel right to us and make us feel good. I know I do. We want to connect emotionally and often want to do more than give cash. The urge to get on a plane and go after an emergency is strong, I’ve done it twice, but 99% of the time, cash is best.

Recently I was with a group of partners from across South East Asia. I heard a story of dolls sent to a Muslim community for children who had been displaced after the 2018 Sulawesi tsunami. The local partners sighed at the thought of the work involved in processing, unpacking and delivering the dolls, especially as they were trying to work out the logistics of food, shelter and medicine. Once the dolls had made their way into the community, it was discovered that when you pressed their bellies, they recited the Lord’s Prayer! The local partners were then accused by government and Muslim leaders of proselytising which is illegal, and almost lost their right to operate in the region.

Because overseas aid can at times do more harm than good and because the international response to the big 2004 tsunami in Indonesia was quite honestly a disaster of its own, the Indonesian Government has rightly banned outside organisations from working there after emergencies without explicit vetting.

Try and imagine every NGO and their branded tents setting up shop after a cyclone. I’ve seen it, it’s a nightmare that often displaces the work of local agencies and mostly serves the priorities of donors and the organisations implementing their funds.

Other partners have told me the Christmas shoe boxes filled with stuff that get sent over to some of their communities often end up in the river or in landfill. They short change the local economy (you can get toothbrushes anywhere in the world) and are confusing for people who don’t celebrate Christmas or who do so without gifts but with ceremony and palm leaves wrapped around poles, and meals made especially for the occasion.

Why do we assume that children are poor because they don’t receive gifts at Christmas?

We need to ask better questions. I’ve needed to ask better questions. Like, how do we support changing the systems that mean that people can’t purchase what they need for their children?

This can be a rough question because it would mean we are no longer in the position of power. People become our equals. We are naturally drawn to this power underlying altruism, as unconscious as it may be. Sit with this for a moment to see if it’s true.

Why not send the funds involved in producing, packing and sending the Christmas boxes, to local organisations working to serve people in their countries? Mostly I think it’s because we want to personally connect and to involve our kids in the tactile act of giving. I get it. I’ve done it. How can we do it differently?

Share the Dignity is asking for toiletries and handbags for homeless Australian women for Christmas, you can drop them into your local Bunnings. Two Good is a company that provides a jar of soup to a person in need for every jar of soup you buy. There are so many other ways our kids can see us act generously and participate locally.

Internationally, get to know and connect with organisations doing good work, teach your kids about them, tell other people, own the story, then support them with cash. (UnitingWorld has just launched an appeal where you can buy gifts-in-kind for Christmas!). Or volunteer with them. If the drive is strong, join the sector. Or test your motivation and ask yourself if perhaps what you want to do is travel and meet people whose lives are different to yours. That was undoubtedly a big part of it for me.

If you go, support local economies and go on a trip that is about solidarity and experience or cultural exchange. Go to see what you can learn. Go where there is an invitation, see where you can come alongside people. Be honest about what you are there for and where its limits begin and end.

“Am I qualified?” is another really great question. You may have seen in the news recently a story about a young American woman who went to Uganda and felt called by God to set up a medical clinic, despite having no medical qualifications. More than 100 children died as a result. Can you imagine doing the same thing in your community?

Because we like to “go,” we unknowingly and with good hearts end up building dependence on our skills without building local capacity or the intention to do ourselves out of a job.

Year after year, I watch professionals get grants and raise funds to take groups to communities for much-needed medical and other services over a week or so. They keep going back. What is really wonderful is when these groups train locals to do the same work and invest in training and education over time, reducing the need for outside services. Not only does this build people’s skills and capacity and strengthen their country, it starts to even out the us-and-them dynamic.

If you’re still with me, have a read of this blog by a young Nepalese man who writes strongly about one-week trips to “serve” in Nepal as a way of easing foreigners’ wealth guilt. It’s not an easy read.

He says, “Aid has the potential to overpower and devastate. It can create an imbalance and weaken spirits” And this line made me sit up straight: “If you constantly make people believe that they need help they will make it their ethos in life. In the quest to empower them, you disempower them.”

At a sector conference I attended recently, a powerful young Papua New Guinean woman posed the question from the stage, “who would we be to you if we no longer needed your aid?” Also a really great question. We get used to a certain way of defining ourselves. “First and third world”, “civilised and sh*thole” countries, rich and poor, black and white. Language matters. Dignity matters.

I know of an organisation that created a poverty simulation experience for Western people to go to on a Saturday afternoon in their city.

I would like to suggest a poverty simulator in Sydney of packed-to-the-brim station wagons. The ones white Australian women are living in with their small children to escape domestic violence. People could pay to see the piles of dirty nappies on the ground outside the cars and donated food leftovers rotting alongside. Actors could role play the ways these women have to use toilet paper from public toilets when they are menstruating and children could act out being hungry at school in dirty uniforms. Or perhaps family groups could take evening bus tours of the poorest neighbourhoods in Australia during their annual holidays. They could drive around the streets where homeless people sleep and take photos to show their friends to encourage them to donate.

I hope that sounds deeply offensive to you. People’s poverty is not ours to experience. In simulation or real life. It is never the full story.

My sharpest learning curve has been around my own power. I’m embarrassed to admit that when the topic of racism would come up when my (caramel-skin-coloured) kids were little, I used to say ‘oh I don’t see colour.’ And in my naive way it was true, they were no different or less deserving of anything because of the colour of their skin, which is what I meant. But it’s sort of like when people say, “I can’t be racist because my best friend is black.”

I learnt to stop saying that of my kids, and I understand now that what I was saying is received by people of colour as not seeing them. I didn’t understand the world from their perspective. I thought I did, I had great compassion for suffering, but I had still positioned myself as the one who was coming to fix it. I didn’t acknowledge the world as they experience it. How could I if I wasn’t looking, quite comfortable in my role as saviour? I saw them only as in suffering or poverty. A 12 year-old recently said to me, knowing I was about to travel to Africa, “I hope you don’t get any diseases.” He has absorbed this message too. We must do better.

In this same vein, telling our kids to eat their veg because there are children starving in third world countries is profoundly unhelpful and reinforces the above. Our kids can’t grasp that conceptually, aren’t motivated by guilt and shame and the sassy ones will tell us to pack it up and send it over! We are learning now also that young people are often overwhelmed by poverty and feel something akin to survivor’s guilt. It’s too much and can be traumatic. There are better ways than making them feel bad, to teach them of their privilege and inspire them to become allies.

We play a game with overseas partners where a few people stand on a stage and face two lines formed by the group. The people on stage throw balls deliberately only to the front row. As they are thrown they might call out, “here, have a leadership ball, an education ball, some decision making power balls, wealth balls, some access to health care.”

The people in the back row start to get upset, saying, “hey throw us some balls too,” but the ones in the front are very happy receiving them and quite unaware that there are people behind them not catching anything. We talk about how each row felt and how, for society to become more equitable, the front row needs to give up some of the balls they caught and make space in their line for the people at the back to catch them too.

We like to hold on to our privilege in the front row. How do we start to make space?

I come from the dominant power story, I’m white, educated and middle class and I live in one of the wealthiest countries in the world. As the dynamic of me in the centre started to make me uncomfortable, I had to learn to be quiet. To listen and learn, to be led by people in communities where I found myself working.

My young family moved to Fiji for three years for my then husband’s job. I found my way into a role at the Fiji Red Cross Society that would change everything. I was part of a team delivering health promotion all over the islands and discovered that if you sit on the mat with people long enough, you hear that they already have the answers. I started a Masters in International Health and found that rather than missionary work where I imagined swanning in to save the day, locally-centred and locally-led community development was going to be one of my greatest teachers.

It started to dawn on me that while white and Western colonisation may no longer be happening formally, it continues in the form of outside groups coming in to build structures that are not needed and nobody asked for, by fly-in/fly-out training that places us at the centre and doesn’t build local capacity. By creating attachment issues while visiting children’s homes and taking photos of cute babies for social media, and of those who are vulnerable, without permission or people’s full understanding.

These things would never be allowed in our context, why is it ok in theirs?

I am learning that if I feel uncomfortable about being challenged by those like the Papua New Guinean woman, I am not being oppressed or discriminated against. Reverse racism isn’t a thing. I am just feeling uncomfortable as the dynamics start to shift.

If the way we work for and give to overseas development is above being challenged or held accountable, and was not established at the invitation of local communities (women and men, not just the blokes); it might be unhealthy, dangerous, or worse.

I get to travel a lot, make meaningful connections and meet incredible people. I don’t take the experiences I have had these last 15 years for granted. While NGO travel is the most unglamorous and exhausting thing going, it has been transformative.

But I have learnt the hard way that there are both healthy and toxic ways to engage. As the ones with the power, we must reflect and be prepared to acknowledge that we may have been part of the latter. Certainly, we are part of and benefit from systems that oppress our sisters and brothers around the world.

In truth, I often wonder what my role is in the work I do. I feel so uncomfortable when people tell me it is some combination of virtuous and noble. I know I’m not the amazing one. In my day job, our overseas partners are courageous, resilient change makers; much braver than me, and they’re as far as is possible from the patronising narratives we have allowed ourselves to believe of people living where they do.

Our team finds ways to support what they are doing, offer our friendship, hear their perspectives and ask how we can learn from them in the Australian context.

Our Africa partners break my heart open. They are vibrant, remarkable people who live through trauma and hardship with grace, joy, dancing and community. I am still processing my recent trip to Zimbabwe and Kenya, where we met with our South Sudan partners – and oh my, the thrill of Africa, the powerful Motherland that pulled me in 30 years ago.

Our India and Indonesia partners live in multi-faith, multicultural settings and have learnt to get along together in ways we could really benefit from in Australia.

Our Pacific partners are affecting generational change around gender equality and making space for women’s voices. Our Bali partners are leaders in care for the earth and holistic poverty alleviation.

All of them are facing the accelerated effects of climate change and increasing natural disasters which are undermining good development. They are all just getting on with it, no one is arguing about the science. My job is really to find ways to get them in same room to learn from one another and to know when to pass the mic. To advocate when they ask me to and to help secure funding for their work.

The role of Western people in overseas development is changing, reforming even. Perhaps not fast enough, but it is changing as people find their voices and push back against unhealthy ways of working.

We have a place as allies and partners. May we have the courage to acknowledge our colonialist roots, remove ourselves from the centre and feel a little uncomfortable.

I have a framed quote on my desk by Gangulu woman, Lilla Watson.

She says “If you have come here to help me you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up in mine, then let us work together”

I cried like an idiot the first time I saw this on the wall at another agency, thankful to be on my way home from a meeting. I am acutely aware that my liberation is bound up in that of the people I work alongside. I am better for knowing them and their generous friendship, their gracious tolerance of the times I have messed it up. Their joy in the midst of impossible circumstances and strength that I borrow in facing my own pain.

What I get to do is life changing, but mostly the life being changed is mine.

With love,

Jane

Jane Kennedy

Associate Director

UnitingWorld

You can help fight poverty and build hope with your Christmas gift giving!

Giving gifts from our Everything in Common gift catalogue is a great way to support the work of our overseas partners.

Shop online for gifts like chickens, goats, clean water, education and income opportunities for families to live with dignity. Every gift helps take us closer to the kind of world we all hope for.

Choose a gift. Dedicate it to a loved one. Change lives! Order now online: www.everythingincommon.com.au