Longing for a new season

“For everything there is a season, and a time for every purpose under heaven…

A time for war, a time for peace… A time for mourning and a time for rejoicing…”

They’re words from the writer of Ecclesiastes, but like a lot of people, I heard them first in the classic song ‘Turn, Turn, Turn’ by The Byrds. I was 16, devouring all the classics from the 50’s and 60’s. Pete Seeger’s melodic conjuring of the seasons – nothing out of place, nothing unexpected – was reassuring. It was also biblical: a win win.

Fast forward to the chaos facing so many around the world – an estimated 265 million people are facing acute food insecurity due to COVID-19, for example – and I’m not so sure.

This is a season of suffering, and I want it to end.

I spoke recently to Rev John Yor in South Sudan. The line was terrible – electricity is reliable for only a few hours each morning in the capital Juba – and he’s softly spoken, with an undercurrent of strength that makes you think of the tallest tree in a silent forest. I had trouble hearing everything he said, but what I heard was enough.

He’s put aside two pieces of bread for his dinner, he tells me when I ask about hunger, and will look for more food in the markets with hundreds of others. Food prices, he says, are through the roof. Local crops have been destroyed this year by drought, a locust plague and now flooding; border closures, lockdowns and conflict have choked supplies coming in from Kenya and Ethiopia. In his church compound, he finds people who have walked for days to beg for food, water and shelter. His heart is breaking as he struggles to respond. “We have little but prayer,” he says.

South Sudan’s long season of suffering is well past it’s due date. Her people are vibrant and her land a diamond in the rough, but the country holds the dual honour of being the site of Africa’s longest running civil war and its worst refugee crisis. The causes of this tragedy reach deep into history – Egyptian and British rulers who favoured the north (known simply as Sudan since the South won independence in 2012) and provided basic infrastructure like roads, hospitals and water systems that the South still lacks; brazen raiding of the South for slaves; tribal groups warring over access to land and livestock to feed themselves as natural disasters constantly push the country to the brink of famine.

And now COVID-19. Last year the World Food Bank fed five million people in South Sudan; this year the numbers are expected to double. Mask wearing, soap and water for hand washing – these things are far beyond the reach of ordinary people, even if they had access to the televisions, radios and social media that carry public health messages. In rural areas where Rev John and his team from the Presbyterian Church of South Sudan work, people look to the skies for food drops from the UNHCR. They live in tents and shacks thrown together in places where tribal fighting hasn’t yet left homes looted and burnt. They’ve fled with the clothes on their back and little else. Since 2013, 1.4 million people have become refugees inside the country and another two million live in camps across the border in Kenya and Ethiopia.

I watched a report from Al Jazeera on YouTube that brought the painful reality of life in South Sudan into agonizing focus. And I looked at images sent to us by John and his team of their time in a refugee camp, giving out food, masks, hand sanitiser and clean water. The people they meet simply cannot believe that on top of everything else, a deadly virus stalks their country. South Sudan has 80 beds in its new infectious unit facility, and only one COVID-19 testing center in the capital. John and the Presbyterian Church have been out in communities teaching about social distancing, a massive challenge in place where hundreds of people touch the same bore handle for water and families live shoulder to shoulder under tarps.

“John,” I said to him, heart as low in my chest as it’s been in a long time, “How do you maintain your hope through all this?”

His reply was both as strong and as gentle as his description of South Sudan’s pain.

“I hold close the words of the writer of Ecclesiastes,” he said. “For everything there is a season – a time to be born, a time to die. A time for war, a time for peace; a time to mourn and a time to rejoice. And God has made all things beautiful and set eternity in our hearts.”

This is no wishful thinking – no glib quote to justify an indulgent life backed by the belief that God has everything under control and there’s no need to act.

It’s the lifeblood of a faith that drives a man to risk his life daily for others, alone in a city too dangerous for his family to make their home. It’s the steely heart of a commitment to God’s world and God’s people no matter what; a rock-solid anthem that life can and will be redeemed. It’s the language of call and conviction and all the weight of intimately knowing an unshakeable love that transforms.

It leaves me, to be honest, a bit torn apart. My own faith is a pale shadow in comparison; I have questions and doubts and anger that simmers. I have no doubt John does too.

But John is the man in the moment, the person for whom all this is more than simply a phone call. His eyes are on eternity and his hands and heart are raw from the ruthless realities of here, of now – and still he hopes. Still he proves the presence of Christ, alive and at work in the world, forever faithful.

If that isn’t enough to galvanise us to action, then what is?

Life in Australia has its own share of sorrows right now: there’s a breath-holding claustrophobia as case numbers rise and fall and many of us remain locked away from each other and our ordinary dreams of work, family, future. Part of the antidote to this suffering is opening the window to a bigger picture, a wider world into which we’re woven through our shared experiences of loss and love. John’s voice, the steadfastness of Christian people scattered throughout South Sudan, India, Zimbabwe, Indonesia – these are the flickers of hope that warm us, the places where we see God’s presence in the midst of absolutely ordinary people like us.

We might long for a new season, but the truth John and others reveal is that whatever our pain, whatever our joys – God is present and God’s people are faithful. Our brothers and sisters in South Sudan call us to a season of steady determination, the bending of our hands and hearts to give and pray and reflect, the quiet faith that grows with solidarity. It feels familiar, but with each story we collect of ordinary people caught up in the extraordinary, it becomes new. There’s strength in that. It’s enough.

Our church partners in South Sudan are racing against the clock to get food and water to people in lockdown and in refugee camps, and providing masks, sanitiser and health messaging. Please give, pray and learn from our Christian brothers and sisters in South Sudan here: www.unitingworld.org.au/southsudancrisis

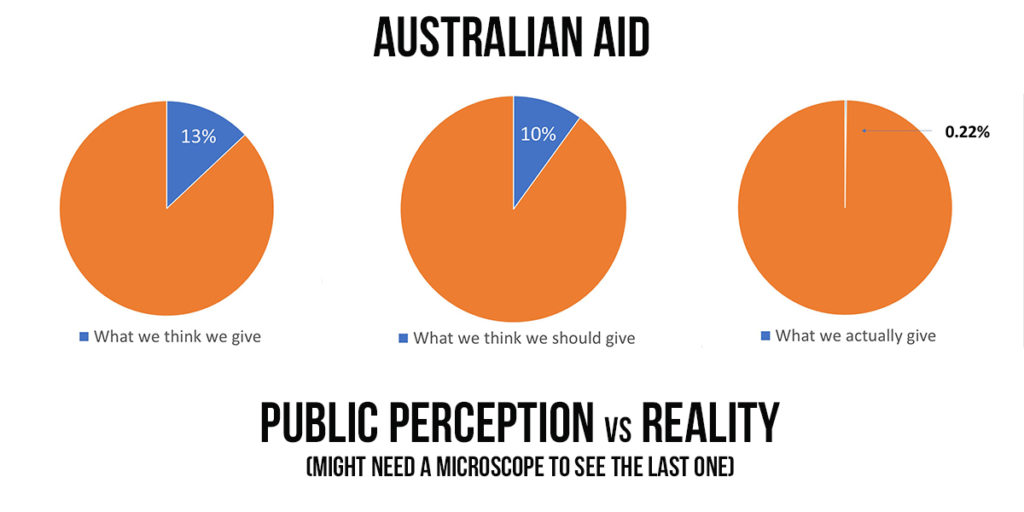

Actually, there is. But it means each of us continuing to embrace the vision of ‘together’ and walking away from the fear that makes us wonder if we have the means to look after anyone but ourselves.

Actually, there is. But it means each of us continuing to embrace the vision of ‘together’ and walking away from the fear that makes us wonder if we have the means to look after anyone but ourselves.

Although we may not be able to gag Mother Nature, we have been given the means to prevent these disasters before they become sixteen-million-life tragedies. After all, we know that monsoon rains will reliably take the lives of men, women and children in India, Bangladesh and Nepal, year after year, simply because they live in low lying areas, in homes that are badly built, beside rivers that will swell and swallow them whole: they’re too poor to move elsewhere. It won’t be flooding that kills these people and their livelihoods. It will be the lack of evacuation plans, poor communication, homes built on the side of mountains where they shouldn’t be, and outbreaks of disease. In short, it’ll be poverty, and the lack of opportunity that comes with it.

Although we may not be able to gag Mother Nature, we have been given the means to prevent these disasters before they become sixteen-million-life tragedies. After all, we know that monsoon rains will reliably take the lives of men, women and children in India, Bangladesh and Nepal, year after year, simply because they live in low lying areas, in homes that are badly built, beside rivers that will swell and swallow them whole: they’re too poor to move elsewhere. It won’t be flooding that kills these people and their livelihoods. It will be the lack of evacuation plans, poor communication, homes built on the side of mountains where they shouldn’t be, and outbreaks of disease. In short, it’ll be poverty, and the lack of opportunity that comes with it.